This one goes out to the Art Evolved krew. You freaking maniacs!

This post is a response to this post.

STONES

An Unfinished and Very Rough Test-Boring

for the Next Draft of the Film Script

Gene Skinner left the service in twenty-forty-eight with a strong taste for crank, a gun capable of taking out hundred-foot long creatures that looked like a cross between a centipede and a loading dock, a nanite infection comprising twenty per cent of his body weight, and a chronic inability to give a shit about any situation that didn’t involve the possibility of death. Tall and athletic with a shaved head and eyes like coin slots filled with malice, Skinner was the kind of man whose silent twitchy presence discouraged conversation.

Skinner met Randall Duke on a refugee shuttle bound for Morrison Seven, a frontier timeline branched off the late Jurassic. The shuttle had been donated by some aliens who were much larger than humans; the brushed aluminum ceiling was thirty feet overhead while the white floor was dotted with hollows like an egg carton, each hollow fifteen feet across. Families and other social constructs took to the hollows while the rogues and lone-wolf types stalked back and forth under the dull reddish light and social services stayed behind their counters up near the pilot’s cabin where it was safe.

Skinner had spotted a group of USAnian teenagers sharking an Uzbek family for their travel rations; despite the last five presidencies and his tour of duty in the Mechazoic Settlement Conflict Skinner still harbored a vestige of patriotism and the sight before him offended his sense of the USA as a force for good in the multiverse.

Skinner made a point of looking elsewhere while he drifted towards the hassle on casual feet but there was no way he could avoid seeing Duke. Six foot six and an easy five hundred pounds, Duke had receding red hair, pale blue eye and a Fu Manchu mustache. Skinner stopped to take in the spectacle when Duke picked up a problem teen in each hand and began to engage in a little wall-to-wall social engineering.

Skinner had a reputation as a combat artiste in some pretty rarified circles; that didn’t stop him from appreciating the work of a gifted amateur. He didn’t step in until a couple of youths had managed to work their way behind Duke. Skinner didn’t kill them – the Uzbek kids were watching – so they were still making noises when Duke turned around.

The fat man took things in quickly and stretched out a hand to Skinner, who shook it. That was five years ago. These days they had a small but sturdy reputation on Morrison Seven – for a certain type of job a smart organism hired Skinner and Duke.

The Transit Authority building in New Deseret was built in the traditional style, one originally developed to be the boot of an orbital tower, a vast coliseum-type structure covered in the matte green panels of algae farms, the produce of which was used in TA relief efforts. Of course no one was going to be building an orbital tower in Utah – sometimes it was hard to tell the difference between tradition and humor when you were dealing with the TA. Morrison Seven wouldn’t have direct access to the Transit system until its refugee population built their own tower and that wasn’t going to happen any time soon.

The Transit cop’s processor was made out of about three tons of molten osmium interfaced with a temperature-resistant fluorocarbon atmosphere, the whole thing powered by masers, scanned by gravity wave detectors, and contained in the electron cloud of an artificial macro-atom five yards across. That kind of baroque engineering made Skinner think the cop was further up in the TA hierarchy than his (it used a male voice) job would suggest.

“You know anything about the gastrolith trade?” The voice seemed to emerge from the swirl of foamy vortices in the white-hot metal; again, nicer tech than you’d expect from a Transit cop, most of whom were smooth beige trashcans on treads. He used a vernacular that was calculated for compatibility with that of Skinner and Duke; Transit Authority were good people, assuming ‘people’ was the right word.

Duke stroked his mustache with thumb and forefinger and frowned. “It’s a Magpie thing, right? Sauropod gastroliths. They use them for making a tonic or something, pay pretty good money.”

“Boner pills,” Skinner said.

Duke looked at him and lifted one eyebrow, a move Skinner had caught him practicing in the mirror more than once.

“They use them to make boner pills. Like Viagra or rhino horn or something.”

Rhinos had been extinct in Skinner’s home timeline for quite a while but everywhen they were still alive people were shooting them for the horns. Some things don’t change.

“That’s right,” the Transit cop said and swirled so the osmium splashed against the walls of the macro-atom, keeping the complex patterns of thought in motion. “Just like rhino horn; there’s no pharmaceutical effect. The thing is that the hunters who go out after the gastroliths? Over time about seventy per cent of them don’t come back.”

“It’s the Jurassic,” Duke said. “What do you expect?”

“A long-term thirty per cent fatality rate. We don’t make mistakes about this kind of thing. And since the gastroliths move through the Transit system this is under my jurisdiction.”

“Okay,” Duke said. “What do you want us to do about it?”

“For now I want you to sign up as stone hunters and do what comes naturally. I’m not expecting you to solve this, just help me gather information.”

Skinner held up his hand, made an opening in the conversation. “What about pay?”

“I can stake you a camper and gear for now. When you’re done we’ll take a look at how things work out.”

Duke shifted uneasily in his chair. “Well,” he said.

“If you find out what’s happening to those prospectors I can promise you an upgrade on your transit cards.”

Duke perked right up. “I think that could work for us,” he said.

The market was one of the only public spaces on Morrison Seven where you could meet non-humans. It was a flat span of hard-packed red dirt that had been part of the fern prairies ten years ago; by now it had been trampled and worked over and the only plants you could see were milkweed and wild oats. More refugees crowding out the natives.

Overhead a tethered dome was held aloft by hot air; in its shadow were businesses run from stands and shanties, tents and prefab office buildings and the occasional ratty sleeping bag covered with someone’s last few possessions. It took Skinner and Duke nearly half an hour to find a Magpie working the gastrolith trade.

“You is verification,” Mr. Big Johnson said and gestured with one wing toward the camera on the table in front of his perch. His voice was, for the moment, the same as Duke’s.

Skinner thought he was trying to be a pain in the ass; it went along with his perch and his human name. Magpies were as comfortable on the ground as humans were but whoever had the highest head had the highest status. Sitting on a perch was like a short man wearing lifts.

The Magpies were dinosaurs from a timeline where the asteroids that caused the Cretaceous extinction had been nuked until they missed the Earth. They were descended from arboreal maniraptorans who had left the forests for the savannahs. They had black-and-white feathers and the faces of toothy owls along with the typical maniraptoran sickle-claw. They weighed about thirty pounds each and were still capable of limited flight. Despite these exotic details their evolutionary history had given them social and personal characteristics that were as close to human as it got. In other words you couldn’t trust them for shit.

“Digital records for the purposes of lying, my friends. We use old analog tech of your noble people, photochemical emulsion on plastic film in sealed canister. We develop ourselves and for sure you bring us the gizzard stones and not some river trash, you know? Any round rock it will not do.” Mr. Big Johnson opened his snub beak to show sharp little teeth and bobbed his head up and down. “Ha-ha-ha!”

Mr. Big Johnson’s assistance animal picked up the camera and held it out to Duke. It was another feathered dinosaur with a silvery Magpie control blob on the side of its head, feathers patterned in green and tan with a cream-colored underbelly. This one was a local, something like the fossil Ornitholestes, and despite their similar size and body shape it was as closely related to Mr. Big Johnson as rat-headed Purgatorius was to Skinner and had an IQ slightly inferior to that of a chicken. It opened its long, narrow jaws and echoed its boss in a parrot-squawk imitation of Duke.

“Ha-ha-ha!”

The auto EQ in Skinner’s earplugs reduced the sound of the chainsaw to the same level as the buzzing of the insects swarming around the dead saddleback and the Coollar around his neck kept him from dropping in the Jurassic heat. Duke claimed he preferred Kool Kuffs but Skinner thought that was just because Duke was a head-and-shoulders guy – no neck. Either way the tech was simple – refrigerated bands of metal wrapped close to the blood vessels of the neck or wrists.

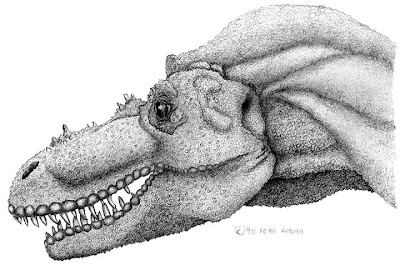

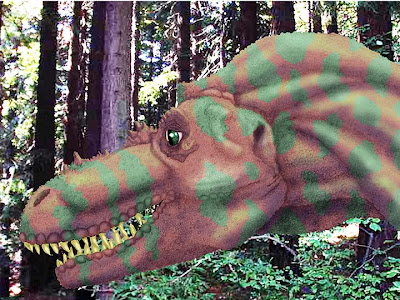

The saddleback was a diplodocoid more than a hundred feet long, named for the sage-and-rust markings that broke up its vast profile. In the promotional literature Mr. Big Johnson had given them along with their contract saddlebacks had been identified with the fossil Seismosaurus; this reinforced Skinner’s doubts about the whole scene. It smelled like false authority. No field scientist would ever try and match a living thing to a fossil. Seismosaurus was a name attached to some hundred and fifty million year-old bones. Skinner had shot the saddleback only twenty minutes ago.

And now Duke was cutting it up while Skinner stood on top of its ribcage, keeping watch. He had combat spex over his eyes and they were getting a feed from the sight of his gun, vision going up into the ultraviolet and down into the infrared. The dusty smell of cedars was in the breeze, coming from a line of trees following a nearby river. The ferns were brown and crisp at their crowns but there was green at their bases. It was still early in the dry season.

The sound of the chainsaw cut off and Duke hollered up at Skinner. “This ain’t no job for a fat man!”

“If you didn’t bitch so much you’d be done by now.” Skinner scanned methodically from his feet to the horizon, then shifted position and did it again. “You want a Stern Fellow?”

Duke wiped his hand on his pants, then swiped his hand across his forehead, splattering drops of sweat against the dusty ferns. “Fuck no. I want to sleep tonight. Hey, you take your pills today?”

“Yes, I took my pills,” Skinner said. As if he needed to be told…

“Don’t be touchy. I just don’t want to be stuck out here with the gray goo is all.”

Gray goo. That term wasn’t just out of date, it was fucking antiquated. For some reason that got under Skinner’s hide – being told he might turn into gray goo was like being told he had dropsy or scrofula. What Duke didn’t get was that the nanite infection wasn’t a disease.

It was a feature.

Duke was getting the gastroliths out of the saddleback. He’d set up the camera Mr. Big Johnson had given them and was cutting a channel through the beast’s chest with the chainsaw and a pitchfork. A blue tarp was spread on the ground, ready to receive the gizzard. Duke was about to start up the chainsaw when Skinner hissed and made a cutting motion with his free hand.

There was the sound of a distant engine. Skinner spotted a dark shape in the sky that wasn’t a pterodactyl. As soon as his eyes focused on the shape the spex acted as binoculars and gave him a clean image of an ultralight, a big triangular wing with a man and an engine slung underneath.

“Didn’t take long to find us,” Skinner said.

Duke spat. “I bet you five bucks they’ve got a bug in the camera.”

Skinner nodded and scrambled off the saddleback...

Skinner met Randall Duke on a refugee shuttle bound for Morrison Seven, a frontier timeline branched off the late Jurassic. The shuttle had been donated by some aliens who were much larger than humans; the brushed aluminum ceiling was thirty feet overhead while the white floor was dotted with hollows like an egg carton, each hollow fifteen feet across. Families and other social constructs took to the hollows while the rogues and lone-wolf types stalked back and forth under the dull reddish light and social services stayed behind their counters up near the pilot’s cabin where it was safe.

Skinner had spotted a group of USAnian teenagers sharking an Uzbek family for their travel rations; despite the last five presidencies and his tour of duty in the Mechazoic Settlement Conflict Skinner still harbored a vestige of patriotism and the sight before him offended his sense of the USA as a force for good in the multiverse.

Skinner made a point of looking elsewhere while he drifted towards the hassle on casual feet but there was no way he could avoid seeing Duke. Six foot six and an easy five hundred pounds, Duke had receding red hair, pale blue eye and a Fu Manchu mustache. Skinner stopped to take in the spectacle when Duke picked up a problem teen in each hand and began to engage in a little wall-to-wall social engineering.

Skinner had a reputation as a combat artiste in some pretty rarified circles; that didn’t stop him from appreciating the work of a gifted amateur. He didn’t step in until a couple of youths had managed to work their way behind Duke. Skinner didn’t kill them – the Uzbek kids were watching – so they were still making noises when Duke turned around.

The fat man took things in quickly and stretched out a hand to Skinner, who shook it. That was five years ago. These days they had a small but sturdy reputation on Morrison Seven – for a certain type of job a smart organism hired Skinner and Duke.

***

The Transit Authority building in New Deseret was built in the traditional style, one originally developed to be the boot of an orbital tower, a vast coliseum-type structure covered in the matte green panels of algae farms, the produce of which was used in TA relief efforts. Of course no one was going to be building an orbital tower in Utah – sometimes it was hard to tell the difference between tradition and humor when you were dealing with the TA. Morrison Seven wouldn’t have direct access to the Transit system until its refugee population built their own tower and that wasn’t going to happen any time soon.

The Transit cop’s processor was made out of about three tons of molten osmium interfaced with a temperature-resistant fluorocarbon atmosphere, the whole thing powered by masers, scanned by gravity wave detectors, and contained in the electron cloud of an artificial macro-atom five yards across. That kind of baroque engineering made Skinner think the cop was further up in the TA hierarchy than his (it used a male voice) job would suggest.

“You know anything about the gastrolith trade?” The voice seemed to emerge from the swirl of foamy vortices in the white-hot metal; again, nicer tech than you’d expect from a Transit cop, most of whom were smooth beige trashcans on treads. He used a vernacular that was calculated for compatibility with that of Skinner and Duke; Transit Authority were good people, assuming ‘people’ was the right word.

Duke stroked his mustache with thumb and forefinger and frowned. “It’s a Magpie thing, right? Sauropod gastroliths. They use them for making a tonic or something, pay pretty good money.”

“Boner pills,” Skinner said.

Duke looked at him and lifted one eyebrow, a move Skinner had caught him practicing in the mirror more than once.

“They use them to make boner pills. Like Viagra or rhino horn or something.”

Rhinos had been extinct in Skinner’s home timeline for quite a while but everywhen they were still alive people were shooting them for the horns. Some things don’t change.

“That’s right,” the Transit cop said and swirled so the osmium splashed against the walls of the macro-atom, keeping the complex patterns of thought in motion. “Just like rhino horn; there’s no pharmaceutical effect. The thing is that the hunters who go out after the gastroliths? Over time about seventy per cent of them don’t come back.”

“It’s the Jurassic,” Duke said. “What do you expect?”

“A long-term thirty per cent fatality rate. We don’t make mistakes about this kind of thing. And since the gastroliths move through the Transit system this is under my jurisdiction.”

“Okay,” Duke said. “What do you want us to do about it?”

“For now I want you to sign up as stone hunters and do what comes naturally. I’m not expecting you to solve this, just help me gather information.”

Skinner held up his hand, made an opening in the conversation. “What about pay?”

“I can stake you a camper and gear for now. When you’re done we’ll take a look at how things work out.”

Duke shifted uneasily in his chair. “Well,” he said.

“If you find out what’s happening to those prospectors I can promise you an upgrade on your transit cards.”

Duke perked right up. “I think that could work for us,” he said.

***

The market was one of the only public spaces on Morrison Seven where you could meet non-humans. It was a flat span of hard-packed red dirt that had been part of the fern prairies ten years ago; by now it had been trampled and worked over and the only plants you could see were milkweed and wild oats. More refugees crowding out the natives.

Overhead a tethered dome was held aloft by hot air; in its shadow were businesses run from stands and shanties, tents and prefab office buildings and the occasional ratty sleeping bag covered with someone’s last few possessions. It took Skinner and Duke nearly half an hour to find a Magpie working the gastrolith trade.

“You is verification,” Mr. Big Johnson said and gestured with one wing toward the camera on the table in front of his perch. His voice was, for the moment, the same as Duke’s.

Skinner thought he was trying to be a pain in the ass; it went along with his perch and his human name. Magpies were as comfortable on the ground as humans were but whoever had the highest head had the highest status. Sitting on a perch was like a short man wearing lifts.

The Magpies were dinosaurs from a timeline where the asteroids that caused the Cretaceous extinction had been nuked until they missed the Earth. They were descended from arboreal maniraptorans who had left the forests for the savannahs. They had black-and-white feathers and the faces of toothy owls along with the typical maniraptoran sickle-claw. They weighed about thirty pounds each and were still capable of limited flight. Despite these exotic details their evolutionary history had given them social and personal characteristics that were as close to human as it got. In other words you couldn’t trust them for shit.

“Digital records for the purposes of lying, my friends. We use old analog tech of your noble people, photochemical emulsion on plastic film in sealed canister. We develop ourselves and for sure you bring us the gizzard stones and not some river trash, you know? Any round rock it will not do.” Mr. Big Johnson opened his snub beak to show sharp little teeth and bobbed his head up and down. “Ha-ha-ha!”

Mr. Big Johnson’s assistance animal picked up the camera and held it out to Duke. It was another feathered dinosaur with a silvery Magpie control blob on the side of its head, feathers patterned in green and tan with a cream-colored underbelly. This one was a local, something like the fossil Ornitholestes, and despite their similar size and body shape it was as closely related to Mr. Big Johnson as rat-headed Purgatorius was to Skinner and had an IQ slightly inferior to that of a chicken. It opened its long, narrow jaws and echoed its boss in a parrot-squawk imitation of Duke.

“Ha-ha-ha!”

***

The auto EQ in Skinner’s earplugs reduced the sound of the chainsaw to the same level as the buzzing of the insects swarming around the dead saddleback and the Coollar around his neck kept him from dropping in the Jurassic heat. Duke claimed he preferred Kool Kuffs but Skinner thought that was just because Duke was a head-and-shoulders guy – no neck. Either way the tech was simple – refrigerated bands of metal wrapped close to the blood vessels of the neck or wrists.

The saddleback was a diplodocoid more than a hundred feet long, named for the sage-and-rust markings that broke up its vast profile. In the promotional literature Mr. Big Johnson had given them along with their contract saddlebacks had been identified with the fossil Seismosaurus; this reinforced Skinner’s doubts about the whole scene. It smelled like false authority. No field scientist would ever try and match a living thing to a fossil. Seismosaurus was a name attached to some hundred and fifty million year-old bones. Skinner had shot the saddleback only twenty minutes ago.

And now Duke was cutting it up while Skinner stood on top of its ribcage, keeping watch. He had combat spex over his eyes and they were getting a feed from the sight of his gun, vision going up into the ultraviolet and down into the infrared. The dusty smell of cedars was in the breeze, coming from a line of trees following a nearby river. The ferns were brown and crisp at their crowns but there was green at their bases. It was still early in the dry season.

The sound of the chainsaw cut off and Duke hollered up at Skinner. “This ain’t no job for a fat man!”

“If you didn’t bitch so much you’d be done by now.” Skinner scanned methodically from his feet to the horizon, then shifted position and did it again. “You want a Stern Fellow?”

Duke wiped his hand on his pants, then swiped his hand across his forehead, splattering drops of sweat against the dusty ferns. “Fuck no. I want to sleep tonight. Hey, you take your pills today?”

“Yes, I took my pills,” Skinner said. As if he needed to be told…

“Don’t be touchy. I just don’t want to be stuck out here with the gray goo is all.”

Gray goo. That term wasn’t just out of date, it was fucking antiquated. For some reason that got under Skinner’s hide – being told he might turn into gray goo was like being told he had dropsy or scrofula. What Duke didn’t get was that the nanite infection wasn’t a disease.

It was a feature.

Duke was getting the gastroliths out of the saddleback. He’d set up the camera Mr. Big Johnson had given them and was cutting a channel through the beast’s chest with the chainsaw and a pitchfork. A blue tarp was spread on the ground, ready to receive the gizzard. Duke was about to start up the chainsaw when Skinner hissed and made a cutting motion with his free hand.

There was the sound of a distant engine. Skinner spotted a dark shape in the sky that wasn’t a pterodactyl. As soon as his eyes focused on the shape the spex acted as binoculars and gave him a clean image of an ultralight, a big triangular wing with a man and an engine slung underneath.

“Didn’t take long to find us,” Skinner said.

Duke spat. “I bet you five bucks they’ve got a bug in the camera.”

Skinner nodded and scrambled off the saddleback...